The world of the renowned Texas philanthropists and collectors, Dominique and John de Menil, was enigmatic. Starting in the 1930s, they embraced several social and political causes in Europe and America while building a vast and varied art collection. After John’s death in 1973, Dominique opened the Menil Collection to house their collection near their home in Houston. A new exhibition, The Space Between Looking and Loving: Francesca Fuchs and the de Menil House on view through November 2, explores the distinct way the Menils lived and collected, centering unseen connections through times and places, people, regions, mediums, and cultures. Between rare images of the Menil’s home hang Fuchs’s acrylic paintings and sculptures, made in response to the Menil’s archive, which the artist spent days poring over, photographing, and interpreting.

“We are known for shows where artists come and investigate the collection,” says Paul Davis, curator of the exhibition. “That goes back to Andy Warhol’s Raid the Icebox. The way Francesca has done it is really unique and introspective and has revealed a lot about the sentimentality of the Menil collection. What is often talked about in the abstract she has made concrete and poetic.”

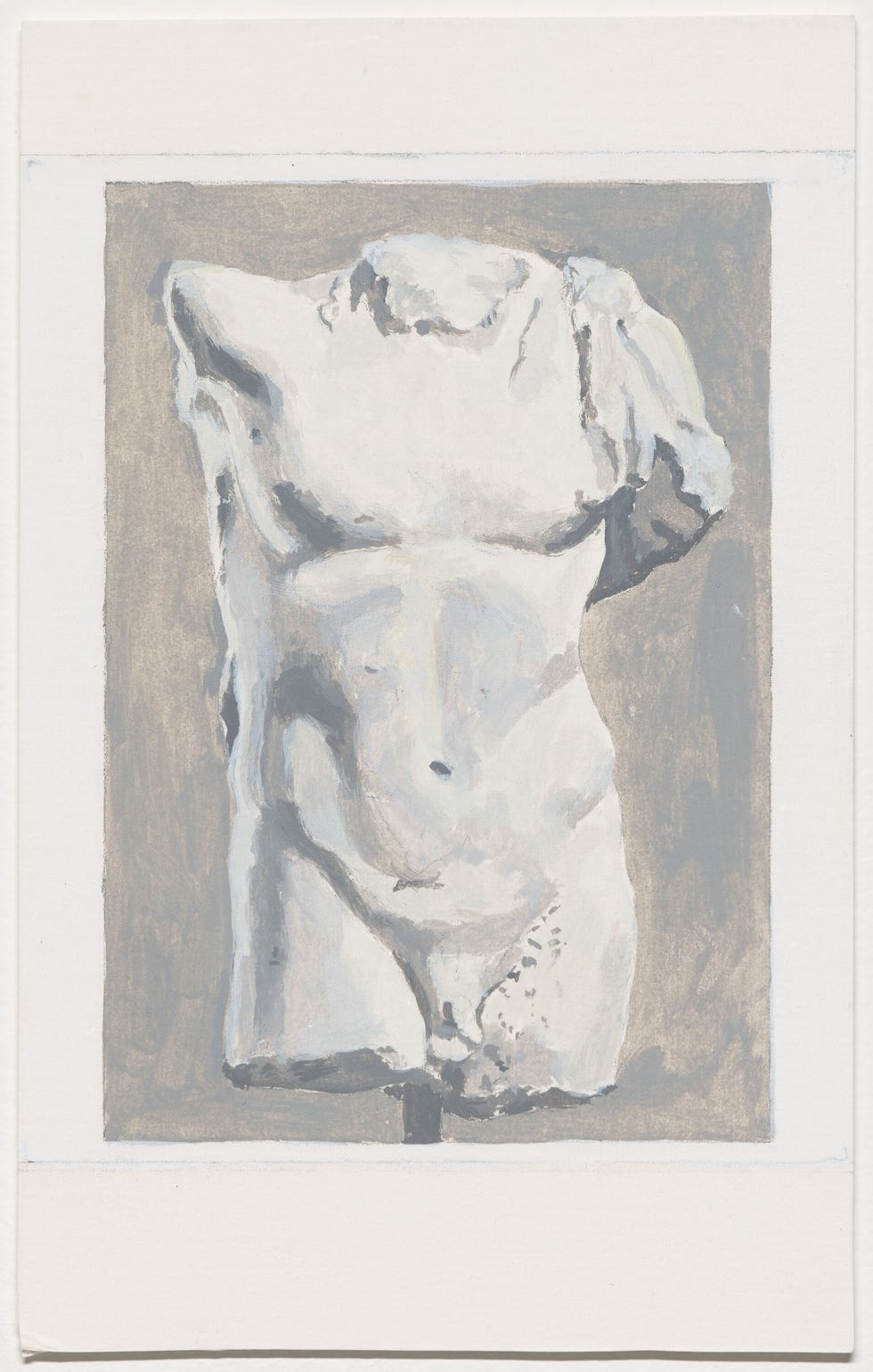

The story of how the show came to be involves a series of coincidences. Fuchs, who is Houston based, was born in London, in 1965, and raised in Münster, Germany, where her father, Dr. Werner Fuchs, worked in classical archeology. It wasn’t until 1996 that the artist moved to Texas as a fellow at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Many years later, as she went through her late father’s personal effects, she found a black and white photograph of a classical male torso. “I turned the image over and it said Rice University, Menil Collection,” says Fuchs.

She had no idea how her father ended up with it. What she did know was that John de Menil had written to her father with the hope that he could help identify a male torso he’d acquired. Fuchs’s father never responded. 49 years later, Fuchs decided to seek out a copy of the letter de Menil had sent, which she found during her research in the Menil archives.

“My work is really about these love connections,” says Fuchs. “Real connections to objects and people; the serendipitous.” Dominique and John de Menil’s connection was very much about love. But not just love for each other, love for their community and the artists and people who showed them new ways of life.

Their home was a testament to the many perspectives and places that influenced their personal philosophy. It was built for the Menils in 1948 by Philip Johnson. Clean, minimal, flat-roofed, with a glassed-in interior courtyard and ample space for their art and antiques—it was considered shocking at the time. American couturier Charles James, who the Menil’s hired to design their interiors, proved the perfect foil to Johnson’s right angles. James turned his one and only interior design project into an opportunity to experiment wildly with color and texture. The result was a mesmerizing medley that eschewed European and American collecting traditions up until that point. Photographs taken while the Menil’s inhabited the house show James’s Lips sofa mingling with curvaceous 19th century chairs, Oceanic and African art, 15th century angels, tiger skins, Rene Magritte paintings, and John’s 18th century French desk. Fuch’s exhibition responds to this singularity, offering a meditation on the space between an original and a copy. Her work explores the interpretative faculties involved in every reproduction and what information can be gleaned from variance. Put simply, The Space Between Looking and Loving: Francesca Fuchs and the de Menil House examines relationships: between Dr. Fuchs and John de Menils, between the artist and the Menil Collection, between the painting and the subject, and between the viewer and the artwork.

Visitors to the show can draw the line between looking and loving themselves, with Fuchs’s interpretation of the art and home of the Menil’s, alongside the original objects that birthed this body of work. In one corner of the exhibition Henri Matisse’s Black Leaf on Green Background, from 1952, hangs nearby William Steen’s After Henri Matisse, circa 1995, mimicking the original. Fuchs’s Green Matisse 1 and Red Matisse, made in 2024 continue this thread. Together, the works take viewers on a visual journey that extends over 72 years. (A similar gouache by Matisse in red once hung in the Menil’s kitchen.) In this way, the exhibition makes an argument for the poetic possibilities of simulacra. “I am using painting for the illusionary capacity it has and at the same time showing you the truth,” Fuchs says.

Fascinating ephemera from the Menil’s lives mingle with these works. Paint samples for a chaise longue that James designed for the Menils hang alongside preparatory sketches of the chaise itself. Fuchs’s Pin Door with Label Sketch painting depicts a cork-covered door that Dominique gradually covered with photographs and clippings throughout the last 20 years of her life. The door itself is also displayed, heavy with memory and feeling.

The exhibition is an exercise, for artist, curator, and visitor, in unlearning the norms of arrangement and reconnecting with the emotive power of visual art and the way in which it is displayed, an exercise the Menils famously took part in themselves. “Even when you go into their bathroom, there is an artwork embedded in the wall,” says Fuchs, directly across from the toilet. What might be embarrassing to others, is simply rational and well placed to them. “We have been doing oral histories with people who lived in the house in their youth,” says Fuchs, “One of them talked about how she felt the furniture was placed in a way to create intimacy and revelation.”

The Menil’s and Fuchs’s approach to life carries a lesson: What would our homes look like if we decorated them purely out of love and a desire to really see, understand, and appreciate what was within them? What would our lives look like if we danced to the beat of our own drums?